Gail E. Radcliffe, Ph.D., is President of Radcliffe Consulting, Inc. (RCI), a team of regulatory, clinical, and business experts that guide IVD (in vitro diagnostic) manufacturers through the complex process of navigating U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European Union regulations to bring their regulated products to market. The company offers regulatory strategy and submission drafting, clinical trial conduct, and assistance with quality system development and implementation.

In this question-and-answer article, Radcliffe discusses the IVD market with Healthcare Packaging.

Healthcare Packaging (HCP): When it comes to in vitro diagnostics from a medical treatment standpoint, how important are IVDs and what should enthuse the general public about IVDs?

Gail Radcliffe: IVDs are extremely important. Most treatment decisions are based on diagnostic product results. Companion diagnostics kick the bar up even more. Companion diagnostics determine whether or not a patient should be treated with a particular drug and if so whether the dosage will be safe for that person.

HCP: Can you tell us about how companion diagnostics and IVDs are related?

Radcliffe: Companion diagnostics are a subset of IVDs. They are all diagnostic products but they are products that are associated with particular drugs. They are required to be on the label of the drug. So they are a very important, high-risk subset known as Class III products.

HCP: Please describe the IVD classifications.

Radcliffe: An example of a Class 1 IVD product might be a hematoxylin or eosin stain for histology tissue sections. It’s low risk and only requires listing the product with the FDA. There is no FDA submission required.

Class II typically requires a 510(k) submission and that you demonstrate substantial equivalence to another product. A Class II devices is considered moderate risk. You are typically getting results that are used in conjunction with other results, so medical treatment decisions are not solely based on the IVD result. Examples of Class II IVDs, which is the largest category, might include measurement of C-reactive protein or detection of infectious disease analytes.

A Class III product typically generates a very important result. A treatment decision is made based solely on that result. So all companion diagnostics are in this category because they either determine who might respond to a particular drug, the dosage that should be given to a patient or who might experience an adverse reaction from the drug. It’s a high-risk category. Examples of other Class III diagnostic products include infectious disease analytes such as HIV or HCV for blood screening. These require Premarket Approval from the FDA.

HCP: What does FDA want to see for regulatory clearance or approval?

Radcliffe: IVDs typically require clinical performance evaluation data in order to get through the FDA. Manufacturers have to provide analytical and clinical validation results to demonstrate safety and effectiveness of their products. When you are submitting for a 510(k) or a PMA to the FDA for an in vitro diagnostic product, you have to include data. That is the difference between IVDs and medical devices—sometimes a 510K for a medical device does not require clinical trial data. To assess effectiveness of IVDs, you always need some kind of method comparison data.

HCP: Can you provide an example of the range or breadth of IVDs?

Radcliffe: There are simple products such as handheld cards that provide a color reaction. Then there’s a more moderate level, such as immunoassay-type products or molecular diagnostics that provide diagnostic information. The more complex examples would be multivariate index assays that measure expression of 50 or 100 different markers whose results are combined to develop a score. The score is developed according to a complex algorithm.

HCP: What are some of the key growth areas that you see for IVDs?

Radcliffe: The trends these days are more toward point of care, toward making products simpler and easier, and toward getting them into more laboratories. An up-and-coming technology is next-generation sequencing. Single nucleotide changes in certain genes may indicate genetic diseases. Sequencing infectious disease organisms can be done to determine which strain is the causative agent of disease.

For example, there are over 100 different Human Papilloma Virus types and only a subset have been shown to be linked with cervical cancer. It’s important to know the strain to determine if you have a high-risk type or one that causes warts.

HCP: You’ve mentioned that the FDA was trying to exert more pressure to regulate IVD testing. Please describe that situation.

Radcliffe: IVDs can enter the market in the U.S. through two paths. IVDs sold as kits are subject to FDA regulations while laboratories that develop their own tests (LDTs) are regulated under CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments), overseen by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the U.S.

FDA has stated that since laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) are diagnostic products they are subject to FDA regulation; however, FDA has always used “enforcement discretion” and has not sought to regulate LDTs. The complexity of newer IVDs has changed the hands-off attitude. FDA is now saying that more oversight is needed for these complex tests so we will see a dramatic shift in IVD regulation in the near future.

HCP: Does that pit certain segments of the IVD market against one another?

Radcliffe: Yes, it’s manufacturers that have to comply with FDA regulations that feel as though there is a double standard. CLIA requirements are viewed as less onerous than the FDA requirements. Therefore, it takes kit manufacturers longer and it costs more to get their tests on the market. It’s pitting these manufacturers against specialty labs.

HCP: What do you see as the likely end game in this scenario?

Radcliffe: The FDA is very clear. There will be regulation of laboratory-developed tests. We just don’t know when or how.

HCP: What’s the best way to keep updated on this?

Radcliffe: Anyone can sign up for FDA’s daily updates at the FDA CDRH (Center for Devices and Radiological Health) daily update registration page (https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/USFDA/subscriber/new). Of course, trade journals are also important.

HCP: You have mentioned that in general IVDs are regulated by CDRH as medical devices while some are biologics regulated by CBER (Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research). Doesn’t that lead to confusion in the industry?

Radcliffe: It does lead to confusion, but let me give you examples: If the intended use of an IVD is to screen blood for infectious disease agents such as HIV, HBV, or HCV, that test will be performed in the blood bank laboratory. That test is cleared by CBER because it is intended to screen blood for infectious agents.

If the test is intended for diagnostic use, for instance to detect HIV, then it would be performed in the Central Lab and would be regulated under CDRH’s Office of In-Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health, or OIR.

HCP: Does your company get involved in IVD labeling issues, and if so, what are some of the key issues involved in IVD labeling?

Radcliffe: We are involved a lot! This is a big one for packaging. Research Use Only and Investigational Use Only labeling is very, very important, and it is changing. When you are choosing a companion diagnostic product, you have to understand when to use IUO because pharmaceutical companies often think that the IVD that they are using within a study is a tool, but FDA’s viewpoint is that if you are using the diagnostic product in a study then it, too, even if the pharmaceutical company isn’t going to submit that diagnostic for clearance or approval, is still considered investigational. That key piece confuses people quite a bit.

HCP: Please describe RUO and IUO.

Radcliffe: RUO is for research use. This is the stage at which manufacturers are performing studies to understand how a particular biomarker is expressed in normal and diseased states. At this stage, it is also important to optimize the analytical test parameters such as interfering substances, precision, stability, and limit of detection. The next stage of development is to perform a clinical evaluation. This is the stage of testing where the new IVD is compared to a reference diagnosis or another FDA-cleared test. The labeling at this stage would reflect the investigational use of the product—IUO.

Then once you get clearance or approval and the product is used to treat patients, the labeling should comply with 21 CFR 809.10.

HCP: Can you describe how your company typically is involved in consulting or advising a firm?

Radcliffe: We usually work with in vitro diagnostic companies or medical device companies, but we have also worked with pharmaceutical companies that are using companion diagnostics in their drug trials. We get involved at the very early stages of development and often help with market research. We then provide regulatory strategy and clinical development assistance to guide the product through the FDA or EU regulatory processes.

HCP: How is your company involved in IVD labeling?

Radcliffe: We conduct label reviews to make sure that the labeling complies with regulations in the U.S., Europe, and around the world.

In Europe, because of all of the different languages, symbols are used quite a bit. The U.S. is slowly accepting some of the symbols, but you have to be careful. If you are developing product labeling that is designed for use in both the U.S. and Europe, you have to comply with both.

HCP: Is this labeling going on primary or secondary packaging, or both?

Radcliffe: There are very specific requirements for IVD labeling. The regulations take into consideration the size constraints of reagent vials. If the primary package (e.g., vial) is too small then labeling information may be placed on the package insert or on the kit box. Some components may require refrigeration upon receipt. The label on these vials should reflect the storage requirements. We conduct label reviews prior to 510(k) or PMA submission, but our company does not get involved in packaging recommendations per se.

HCP: Can you describe some of the more complex IVDs and their packaging needs?

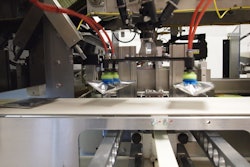

Radcliffe: Many IVDs are packaged as kits with several small vials placed in a polystyrene block, which is inside a box. Some reagents should be shipped frozen (on dry ice), or refrigerated (on ice), which requires special packaging. Once they get to the lab, they may need to be kept refrigerated, so the entire shipping container may be placed in the refrigerator.

Temperature is a common shipping issue, but I have encountered the importance of pressure control during shipping also. I remember having had problems with blister packs shipped by airplane. Tiny leaks were occurring in the blister pack seals when the packs were shipped by air. The temperature and air pressure changes occurring in the belly of the plane caused the seals of the blister packs to fail. We solved this problem with special packaging using hermetically sealed foil outer packages. It was a very specific problem solved by a very specific packaging solution.

(Editor’s note: Click here for specific regulatory details pertaining to IVD regulation.