Packagers knew that we live in an unsafe world long before 9/11. That fact was made painfully clear in 1982 when the Tylenol tampering turned packaging upside down. Who would have imagined that people would tamper with products to harm people they didn’t even know? The alarm was raised and industry—and government—mobilized to make the public all safer from such maliciousness.

In these post-9/11 days, it seems there’s much more to worry about now than back then.

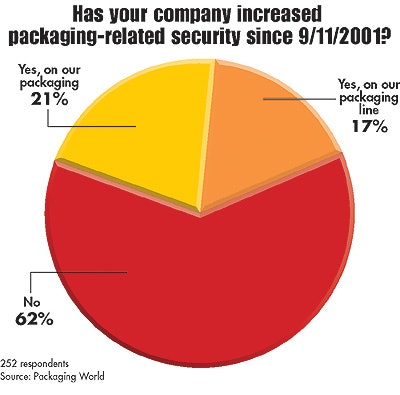

According to an exclusive survey conducted in late spring by Packaging World (see “Methodology” sidebar p.58), nearly 40% of the respondents’ companies have increased their security since 9/11/2001 either in the plant or in their packaging (see Chart 1). Although some of that may have occurred anyway, it seems reasonable to believe that a fair amount is a direct result of the fall of the Twin Towers and the uncertainty that still lingers. It all adds to the complexity of making packaged products safe and secure in 2003. The survey’s popularity, with more than 250 respondents, would also seem to reflect the interest and importance of security for packagers.

A weak link upstream?

For most consumer packaged goods companies, security starts in their packaging operations. For some, concern for security starts even before that. Several respondents from major food companies questioned the security of their incoming raw ingredients when asked, “What do you see as the biggest flaw in safety and security in your and other companies’ products?”

This response from a plant manager at a major food company is indicative of their unease: “In general, ingredients suppliers’ programs appear to be lacking.”

Although not directly packaging, it seems appropriate that improved security of ingredients through packaging may alleviate some of these concerns.

“[Having] so many suppliers makes it difficult to guarantee a secure supply chain,” summed a food research and development manager.

That concern is understandable, especially for parts of the supply chain that packagers have little control over. For the stronger portions of the supply chain under more direct control, packagers employ a range of techniques almost as diverse as their packaging. On production lines, that means metal detectors, X-ray scanners, and the like.

The outbound side of production plants presents an even headier challenge, but packaging offers a number of options. According to survey respondents, the most popular means included those tried-and-true methods of shrink bands and film (Chart 2). Tamper-evident closures and innerseals come next, followed distantly by a range of other packaging methods.

RFID: Stay tuned

A “security blanket” would cover the supply chain from start to finish. One promising and emerging technology that has the potential of doing just that is radio-frequency identification (RFID). Pallets, cases, and even primary packages can be tagged and tracked through a unique identifier, an electronic product code, using a device such as RFID. The process becomes efficient when RFID-tagged products can be read automatically.

According to our survey, RFID is the least used of the technologies, with 1% having reported its use. That will change, likely sooner rather than later. Companies with commitments in RFID include Gillette, which has placed a half-billion order for RFID tags, and Wal-Mart. As announced in June, the retail giant has directed its top 100 suppliers to use RFID devices on pallets and cases by January 1, 2005. Where Wal-Mart goes, others are pulled, though the retailer clarified its position shortly before we went to press after being pressured over privacy concerns (see packworld.com/ go/c082).

Steal sign

Theft concerned a number of respondents. In all, 18% reported their companies have experienced stolen or missing pallet loads of product in the past five years (Chart 3).

A plant packaging engineer noted that “our company logo on the outside of a box is a theft symbol.” When he was asked to elaborate, it was found that he meant that literally: His company ships precious metals, so a 2”x3”x5” box could contain $20ꯠ worth of material, he explained. The company has removed its logo and “genericized” its packaging as camouflage. It also used a tiny electronic tracking device for certain shipments. Along with other methods, that has allowed the company to reduce theft by about 80% over the past several years, he reported. The tracking device helped in a theft case that involved the use of a fake company identification badge and led to the recovery of nearly $150ꯠ of stolen product.

Counterfeiting: The costs

Counterfeiting is an even more insidious security problem that continues to grow. Procter & Gamble’s Gerry Meyer, assoc. director, corporate R&D prototyping and packaging development, spoke at an RFID conference sponsored by Pira Intl. in January (see packworld.com/go/c081). He estimated P&G’s yearly losses attributable to counterfeiting at $225 million, and he pegged the yearly amount worldwide for all packaged goods companies at $200 billion.

Lest you assume counterfeiting is exclusive to pricier items, Meyer pointed out that “no item is exempt from counterfeiters—one of our largest issues is with hair care sachets that retail for less than 10 cents each.” Meyer concluded that “consumers must be engaged in the product authentication process,” thus making a case for overt means. These can include holograms augmented by covert means such as UV inks. Yet, even holograms aren’t a cure-all because counterfeiters have access to such systems.

A growing number of packagers know that counterfeiting doesn’t just happen to the “other guy”: More than 20% of respondents in our survey reported their company’s products have been counterfeited (Chart 4).

Where there’s smoke...

Tobacco products are a prime target of counterfeiters. In fact, a recent report cited cigarettes as the commodity most often seized by U.S. Customs. One manager at a cigarette manufacturer reported that “counterfeit products of inferior quality are showing up at discounted prices. Consumers who purchase these products then complain about the poor quality of our brand.” He said that five years ago it was “very easy to tell fake from real, now the average consumer cannot tell the difference.”

He believed the number of counterfeited cigarettes produced in China alone equals 100 billion per year, or about one-third of the total U.S. market.

He also pointed to the Internet as a boon to counterfeited goods: Consumers see great prices, then receive fake goods. (For further information, search Google.com for “counterfeit packages.”)

Several respondents expressed concern over the trucking portion of the distribution chain, while others mentioned measures they’ve taken to address those concerns. One plant manager noted that his industrial products company provides a metal seal on its trailer doors after loading. Another plant manager with a food company reported that his company applies serial numbers to truck door seals.

In the survey, 8% said their company’s products have been tampered with since 2000 (Chart 5).

Missing, stolen, or counterfeited products all create lost revenue—and sometimes worse. “Our products have been counterfeited and contaminated,” said an engineer at a major coffee company.

Security loopholes

General feelings about security run the gamut. One manager in R&D at a major industrial products company stated with certainty that security was “a very low priority.” Another reported that they see “no problem of safety and security” and that “no flaws exist” in the security of his company’s packaged products. Many packagers would be jealous of such confidence. Others may question their naivete.

The biggest failure in safety and security, according to an engineer with a food company, was “consumer awareness. If someone wants to adulterate a product, it can be done, and too many people still trust that won’t happen. Also, some companies ‘go cheap’ in tamper-evident closures that would be extremely easy to breach.”

A maintenance manager of a medium-sized medical/pharmaceutical manufacturer concurred. “Tampering can be very easily done by anyone who is determined. The end user would likely never detect anything,” she noted.

A plant manager of a private label bottler warns, “You will never stop [people] from tampering with products if they want to.”

An engineer with a West Coast produce packer saw a loophole in “compromises driven by consumer convenience issues.” He felt that consumers pushed packaging to a point where “convenience wins out over safety.”

Self criticism

Several were pretty frank about assessing their own products. Opined a certified packaging professional with a spice company, “My company’s biggest flaw is poor application of TE packaging that defeats its intent. The biggest flaw in general is not educating the consumer as to what to look for in a tampered package.” The engineer felt that for many TE approaches, it’s not obvious to consumers if the package has been tampered with.

It’s sobering to hear a purchasing manager with a major supermarket chain who said “most products are not tamper evident or tamper proof.”

One marketer at a medical-pharmaceutical firm presented this dilemma: “It’s like hackers—the more new security systems are introduced, the more likely someone will try to create a tampering incident.” She suggested that such people have much more serious ways to “make their point” than tampering, a likely allusion to the tragic lesson of 9/11.

“The biggest flaw is companies that do not see the need to make safety and security a major concern,” noted a purchasing manager with a major industrial products company. Emphasized a food plant engineer at a major company, “Upper management’s mentality is that ‘It hasn’t happened to us before, so why should we need to worry about it?’ This is the time to focus on it so it doesn’t happen to our products!”