In 1982, seven deaths were linked to cyanide-laced capsules of Extra-Strength Tylenol. To prevent these kinds of tragedies, pharmaceutical companies spend large amounts of time and money to protect their products from tampering. McCrone Associates occasionally receives examples of suspected product tampering attempts for analysis. The company is typically asked to compare the suspect sample to a pristine sample to look for evidence of foreign materials or physical manipulation of the carton, container, and/or the product.

A visual exam, using both the naked eye and a stereomicroscope, is often the most powerful tool for confirming a product tampering attempt. The analyst compares the physical appearance of each surface of the sample to the reference sample to look for any anomalies. During the microscope exam, a variety of lighting sources are often needed to discern minor differences in texture and color and the presence of foreign materials on the surfaces.

Recently, we received two small [paper]board boxes that had contained bottles of a prescription drug. One box was a customer complaint sample from a suspected tampering attempt, and the second box was from a known good sample. One end of each box was open, and a clear plastic adhesive "tape" strip that was used to seal each box was also present, but had been peeled away from the box surface.

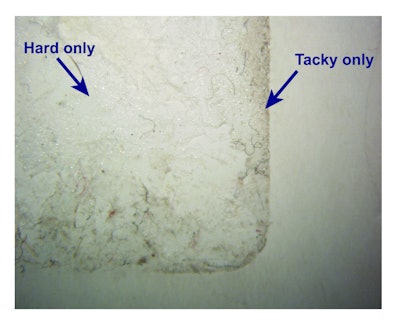

The adhesive surfaces of the tape strips from both boxes were examined, along with the mating flaps of the [paper]board boxes to which the tapes had been affixed. The reference sample displayed a uniform coating of colorless, tacky material on the tape surface, with some paper that had peeled off with the tape, and no adhesive on the mating box flap. The complaint sample tape displayed two materials on the tape surface: colorless tacky material near the edges and hard, shiny, colorless material that was distributed unevenly over the center of the tape—on top of the tacky material. The same hard, colorless material was present in uneven patches on the mating box flap. In some areas of the complaint sample tape, the tape surface displayed areas of hard, colorless material on top of paper that had peeled off with the tape. This suggests that the tape was peeled from the box along with some attached paper, then the hard colorless substance was applied, and the seal was pressed back onto the box. (A photograph of a portion of the box flap or tape from the complaint sample is shown here.)