Delta-style robots can pull off some pretty remarkable feats of packaging, especially when it comes to cartoning of primary packs. A great illustration is the latest installation at contract packager CCB Packaging, where no less than 12 robotic cells are all lined up in a compact row. Designed and supplied by Blueprint Automation, Line 2 lets the Hiawatha, IA-based co-packer put snack pouches or breakfast bars, for example, into top-load cartons of varying sizes at speeds to 150 items/min. Not only can its ABB robots produce multi-flavor variety packs or single-flavor cartons, they can also put different products—like four cereal bars, two oatmeal packs, and some fruit snacks—into one carton.

For a contract packager whose many customers require packaging formats in bewildering varieties, the versatility of the new line is just what the doctor ordered. Key contributions include carton erecting and closing from Kliklok Woodman Packaging Machinery and an array of vision systems from Cognex. Impressive though these may be, what takes the cake in this installation are the 12 feeding systems bringing primary packs to the 12 robots. They, too, come from Blueprint Automation. Installed August 2014 while still in beta phase, the feeders take primary packs from bulk totes and orient them in neatly spaced rows so that the vacuum pick-up cups on the robots can pick and place the packs into cartons moving continuously along a Kliklok Woodman Vari-Pitch conveyor.

“This is brand new feeder technology that we’ve been working on with Blueprint for nearly two-and-a-half years,” says CCB Vice President Frank Cotty. “If the pouches are all clumped together, the robots can’t make a clean pick. We need separation of the primary packages. That’s what these automated feeders provide.”

Certainly helpful in bringing this project to a happy conclusion is the fact that Blueprint and CCB view each other less as vendor and buyer and more as automation/integration partners. They also have a strong track record together, as this represents the third major project on which they’ve collaborated.

Upstream from the robots

The cartons that get robotically loaded are automatically erected on a Genesis top-load, lock-style carton-forming machine from Kliklok Woodman. CCB runs a number of carton sizes on this line, anything from small retail size to larger club offerings, so it’s nice that the machine has a quick-change feed-bar assembly and quick-release plunger tube mountings that allow for fast carton size changeover without the use of tools. The Genesis features twin carton set-up stations, but on the day of our visit a large carton for an 18-count carton was in production, so only one of the carton set-up tools would fit.

One other signature characteristic of the Genesis is that it uses vacuum strip-off for added control of the cartons it erects. Cotty explains.

“Rather than just drop a carton down onto the takeway conveyor, a tool with vacuum cups goes up and strips the carton right off the forming block and guides it down onto the conveyor. The added measure of control helps permit running at higher speeds.”

Erected cartons are released onto a conveyor belt that takes them past a Cognex DataMan 300/360 Series fixed-mount bar-code reader. “It reads a bar code on each carton to confirm that we have the right carton for the product we’re running,” says Cotty. “It’s just in case something happens at the carton converter and a wrong carton gets into the mix. But it also catches any bar code that might be unreadable when it reaches the retailer.”

Cotty says he likes the auto-tuning that’s offered by the Cognex reader, an intelligent tuning feature that automatically selects the optimum settings for the integrated lighting, autofocus, and imager for each application. This auto-tuning process ensures that the bar-code reader will be set up to attain the highest read rates possible.

The flat tabletop conveyor between the carton erector and the first robot provides some measure of accumulation should it be needed. It takes cartons, with covers open, to a tractor index feeder that spaces the cartons for smooth transfer into the Vari-Pitch conveyor that takes the cartons through the 12 robots. The Vari-Pitch conveyor is described by Cotty as a custom-supplied component designed by Kliklok Woodman that isn’t to be found on any other carton loading operation in the world—at least not yet.

“They took the concept of pop-up lugs from their Vari-Straight carton closing equipment and made it into a carton conveyor for us,” says Cotty. “The recipe management system specifies how long the carton is for a particular production run. Based on how long the carton is, the conveyor automatically selects which lugs to pop up. So it brings us automatic pitch change and lets us run a wide variety of carton sizes at linear speeds well within the robots’ abilities to pick and place.

“Because we’re a co-packer with many different customers and products, flexibility is the key. The new line offers the versatility to run a wide range of carton sizes and products along with quick changeover. We package everything from retail-size cartons up to larger variety packs at speeds up to 150 cartons/min.”

The feeding systems

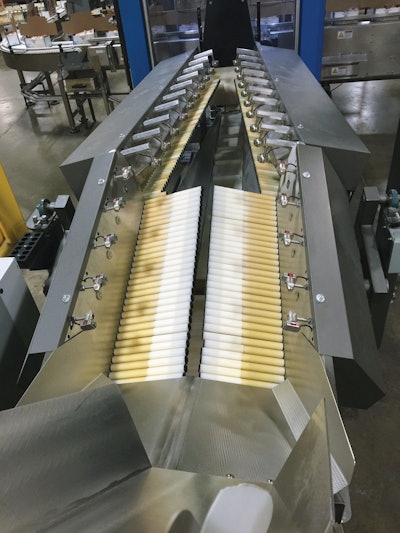

Feeding into the line of robots from a 90-degree angle are the 12 Blueprint Automation feeding systems. Each one operates identically, and each one has 180 white spinning rollers mounted in a stainless steel cabinet, 90 down the left side and 90 down the right. It’s these rollers that both advance the pouches forward and separate them from each other so that the vacuum cups on the delta-style robots can cleanly pick them.

Pouches reach a feeding system by way of a bucket elevator that brings pouches from a floor-level hopper up to a diverter mechanism that pivots left or right depending on whether the left or right side of the feeding system needs pouches. Both sides are identical and operate the same way, but for our purposes here, we’ll follow the left side. Its first section consists of 30 rollers, each about 12 inches long. The rollers are clustered into groups of six, and the rotation of all six is powered by one stepper motor/drive combination having its own controller. Also integrated into each cluster of six rollers is a Keyence sensor that detects where a pouch is positioned relative to the ones around it. This position information is sent to the six-roller cluster’s CPU, which then determines if, based on where the pouches around it are located, it should speed up its six rollers or slow them down. It’s this mutually synchronized modulation of the speed of the six-roller clusters that spaces the pouches out.

Pouches drop next onto a second stretch of white rollers whose diameter is about the same but whose length is about 4 inches shorter than the rollers in the first section. The right end of these rollers is tilted slightly higher than the left, which keeps most of the pouches on the rollers so the pouches can be propelled forward. But there simply isn’t room for all for the pouches, so the ones that slip off the right edge of the rollers land on a floor-level return conveyor from Dorner that reintroduces them into the system by way of the bucket elevator back at the beginning of the feeder system.

A total of 60 rollers are in this second stretch of the feeding system’s left side, and once again each cluster of six includes its own Keyence sensor, its own controller, and its own stepper motor/drive combination. Because each cluster communicates with the ones around it, each controller knows if the overall goal of singulating the flow of pouches will be better accomplished by speeding up its six rollers or by slowing them down.

According to Blueprint Automation CEO Martin Prakken, the feeder system is an example of swarm intelligence: the collective behavior of individual agents, like birds in a large flock, that interact with each other in such a way that synchronized group behavior emerges and the individual agents appear to be one single agent.

“Each cluster of six rollers has its own proprietary algorithm, and each cluster communicates with some of the other clusters immediately ahead and behind it,” says Prakken. He says this new feeding system represents a significant leap forward from the one that Blueprint customers, including CCB, have used in the past. In those earlier applications, the six-roller clusters are driven not by a stepper motor but rather by a servo motor whose drive is back in the main control cabinet. The feeding system’s controller has to communicate with the servo drive and the drive must then communicate with the servo motor. “With this new stepper/drive combo approach and with intelligence built into each cluster of six rollers,” says Prakken, “data flows much more efficiently and quickly”

The net result of the Blueprint feeding system is that in pretty short order what was once a mass of pouches in bulk bins has been converted into an orderly stream of individual pouches that drop from the last cluster of rollers onto a flat pick belt. A vision system, again from Cognex, identifies the precise location of each pouch on this belt and shares these coordinates with the delta-style robot immediately downstream. What happens next depends pretty much on what gets entered into the recipe management system.

“Each of the 12 robotic cells is independent of the others,” says Cotty. “It can feed every carton that goes by, or it can place pouches only into every other carton or every third carton or whatever we choose.”

What it comes down to is that whatever is pickable is fair game. Each cell has three vacuum valve systems, so depending on which tooling is selected each robot can pick up to three items at a time. Pouches can be placed into a carton all at once or one can be placed and then the end effector can be moved slightly to drop the other pouch in a position deemed more favorable. Sometimes this becomes useful in the high-count cartons in order to get them all to fit neatly.

Two other notes on the feeding system. If too many pouches arrive at the pick belt for the robot to handle, the ones that aren’t picked simply drop off the pick belt onto a Dorner conveyor that is connected with the return conveyor leading back to the infeed bucket elevator. Also, if the Cognex vision system sees a pouch that is smaller than the parameters that have been selected—or if it sees a pouch that is crushed or somehow misshapen in a way that makes it unpickable—it tells the robot not to pick that pouch but to let it fall off the pick belt and into the return conveyor. This Dorner conveyor has a pivoting function that is automatically activated to divert the faulty pouch into a reject bin.

Checkweighed twice

Exiting ABB robot #12, the filled cartons convey around a turn and pass over a Mettler Toledo checkweigher. “We checkweigh cartons twice,” says Cotty, “first with the carton still open and then after it’s closed. When it’s open there’s still a chance for a pouch to fall out before reaching the carton closer. Checkweighing after carton closing is one more way of making sure each carton has the correct number of pouches.”

The carton closer Cotty refers to is the Vari-Straight from Kliklok Woodman.

“We have one of the first they ever built on one of our other lines,” says Cotty. “This is the newest version of the Vari-Straight, so it has all Allen-Bradley servo controls. It’s rated at up to 150 cartons/min, and it handles all the carton sizes we do.” The Allen-Bradley controls are supplied by Rockwell Automation.

Integrated into the Vari-Straight carton closer is a Robatech hot melt glue application system. “We found it has such good control of glue and not a lot of adhesive stringing,” says Cotty.“It works great.”

Ink-jet coding of variable information is next, which is done by a system from Domino. “Domino is our partner when it comes to carton printing in this plant,” says Cotty.

Following a second Mettler Toledo metal detector, cartons move next to the EZ Pack case packing station from Combi Packaging Systems. It erects cases automatically and advances them to a station where operators quickly and efficiently load cartons by hand. The cases are then pushed into an automatic top-sealing station where tops are glued closed. A fully automated case packing system was never really an option, says Cotty, because the number of changeovers involved in a co-packing operation like this one would make change part tooling prohibitively expensive.

Case coding is done on an ink-jet system from Squid Ink. Like the upstream Domino system for carton coding, the case coder is told by the recipe management system what information to print each time a change occurs.

Robotic palletizing on a Fanuc system is next. “We installed the Fanuc palletizer in 2007 knowing that we’d want to run a second line into it,” says Cotty. “We also had it designed so that it would pick either corrugated or fiberboard slip sheets. Again, thanks to our recipe management system, the robot knows which kind of slip sheet is called for. Also, if we’re using a corrugated slip sheet, we apply a release glue on each corrugated slip sheet because they don’t have as much tack and that first layer of cases tends to slide around a little bit.”

One improvement in the new line is in end-of-line case handling. On the older line that feeds the palletizer, continuously driven roller conveyors bring cases to the gating mechanism that feeds the cases into the pick station. This allows back-pressure to build up, which can in turn cause the action of the gating mechanism to be compromised. On the new line, the motion of the Hytrol roller conveyors is subject to a PLC that eliminates the back-pressure problem. Also in place is a spur of Hytrol roller conveyor down which cases can be diverted if some sort of special pack-off is required. Once again, having such options comes in mighty handy when you’re a co-packer, says Cotty.

The Fanuc robot, adds Cotty, has run flawlessly since its 2007 arrival. One change made just recently is in the end effector, he adds, where the vacuum plenum has been switched out. Now in place is something called The Squid, a universal vacuum lifting tool from Vacuforce that has a self-closing valve technology enabling individual vacuum suction cups to automatically close if not sealed against the load being handled. So if some of the 120 vacuum cups on the end effector are not in contact with the shipper to be picked, a flapper inside each of those cups’ valves closes to keep dust from entering into that valve. “We made the change about 3 months ago and haven’t had any problems with vacuum since,” notes Cotty. “Before, we’d experience dust-related vacuum problems about every week or so.”

The new line comes to a close with an automated stretch wrapper from Phoenix Wrappers.

Standing at robot #12 and looking back over the other 11 robot cells as they smoothly and automatically go about their business, Cotty is clearly pleased with the outcome of this ambitious and capital-intensive project. “This line continues our commitment to offer automated low-cost packaging alternatives to our customers,” says Cotty. “It’s very high tech.”

Could be the understatement of the decade.