Though there are many reasons that companies resist packaging innovation, careful analysis can yield significant improvements in materials, cost, sustainability and user experience.

At HealthPack 2017 in Denver, Jeff Barnell, Program Manager for Packaging Innovation at Medtronic, offered advice on making device packaging enhancements that truly add value, from using end-to-end financial evaluation to soliciting formal stakeholder input.

As Barnell explained, only two groups touch the finished device—the packout technician placing the device in the open sterile barrier and the scrubbed-in doctors and nurses—while a multitude of stakeholders at the factory, distribution center and treatment facility interacts with the package and label. “Consequently, packaging and labeling teams have the broadest opportunity to innovate due to the diversity of stakeholder needs,” he said.

Barnell offered three examples of device packaging innovation where a robust understanding of all the stakeholder uses lead to new design that relied on material and process selection to maximize the benefits to the business, customer, patient and planet.

Catheter dispenser

A coronary catheter dispenser packaging system is used to protect catheter-based stents and balloons. A plastic tube is coiled and held in place with snap-on clips.

Goal: Create a thinner package to improve customer and distribution center storage efficiency while reducing costs. Because some targeted products come in more than 60 different sizes, thinner packaging would have a big impact on shelf space requirements both in the distribution center and in the catheter lab. Decreasing the volume would further benefit shipping cost and sustainability.

The original package design featured:

-

An extruded LLDPE coiled tubing hoop (12 components)

-

An HDPE accessory holder and accessories (4 parts)

-

Sterile barrier pouch

-

Paper labels and other documentation

-

Shelf carton with film end seal

-

Double wall kraft corrugate shipper

-

Palletizing components

“We identified 26 packaging components originally, so we evaluated each of them to see where we could gain the most benefit,” said Barnell.

Updated Design: By redesigning the dispenser to be molded as one piece, many components were eliminated, most notably the protruding clips that held the tubing in a coil. This in turn lead to a 40% thickness reduction and over 80% reduction in sterile barrier component count. The simplicity and integration improved packaging quality, helped reduce risk, consumed 40% less packaging material and achieved an above-goal cost reduction.

Since a shipper containing 50 of the new packages could be smaller than one containing 30 of the previous design, the redesign also led to a reduction in shipments, logistics transactions and paperwork. Barnell noted that dimensional weight is an important consideration: “It’s the most powerful cost savings tool.”

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) delivery system package

In the case of a heart valve replacement, the previous packaging system required the clinician team to rinse the valve using multiple containers that they supply. Once rinsed, the valve needed to be placed into the delivery system, a somewhat tedious process due to the criticality of the step.

Goal: Leverage the packaging to eliminate the need for separate rinsing containers. Closely evaluate the loading procedure to see how added packaging functionally could benefit this critical step.

Updated Design: Medtronic sought to leverage the packaging to enhance the clinical procedure. The company developed a new nesting, pivoting tray design that functioned as sterile rinsing baths. This in turn eliminated the customer’s expense of providing and sterilizing their own baths. They could improve the loading process by placing a mirror within the tray allowing the doctors to more easily see that the device was loaded properly, reducing the risk of a mistake.

To achieve the desired depth and shape, a new tray material needed to be tested and validated. Though the new material was more expensive, it was justified because of its moldability and toughness. Extensive customer studies showed that the new design performed better than the previous arrangement.

Barnell explained that this is a good example of how listening to your stakeholders, in this case, the healthcare provider, allows you to “create value through packaging.”

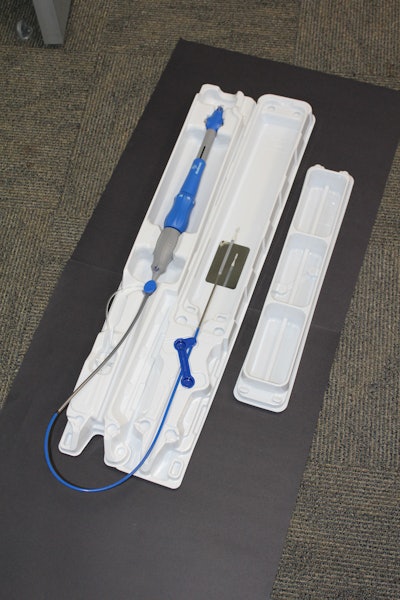

Long catheter stent graft

When a patient is at risk of experiencing an aortic aneurism rupture, every second in the emergency room is critical. Transcatheter aortic stent grafts allow the weakness in this vital arterial wall to be repaired quickly and without traumatic open heart surgery. By first making an incision just below the groin, the cardiologist uses a delivery system to deploy the stent graft across the damaged region. Delivering it aseptically into the sterile surgical area while simultaneously removing the delivery system from its multilayer sterile barrier becomes an intense and highly scrutinized task for the nursing team. The fact that the instrument can be up to 6-feet long, flexible and heavily weighed at just one end adds to the challenge.

The multilayered packaging generates a significant amount of non-recyclable waste including much that must be incinerated.

Goal: Improve the ease and speed in which the device can be delivered into the sterile field while reducing the chance of device contamination. Reduce both the volume and non-recyclable packaging content.

Updated design:

The new design in development consists of a molded tray combined with an extruded tube and cap. Designed to accept a sealed lid, this combination eliminates the need for a sterile barrier pouch and a full length sealer. A key feature of the design is it now allows the nursing team to confidently and quickly open the sterilized package and then hand off the instrument containing the stent graft into the sterile field. The rigid tray serves as grip, comfortable for even very petite staff members. A specialized handle within the tray minimizes the chance of contamination while allowing the receiving nurse to quickly transfer the device, a difference of originally 60, now 8 seconds. The new solution of the former non-recyclable pouch, incinerated tray and carton is now 50% lower volume and 100% recyclable. Literally, twice as many products fit in the original shipping container.

A thorough understanding of the customer’s interaction with the packaging combined with properly selected materials and processes drove the final design.

End-to-end cost evaluation

An end-to-end evaluation should include:

-

Packaging costs (such as materials, labor, burden)

-

Distribution costs (such as shipping, inventory, refurbishment, sustainability)

It’s important to be realistic, and as comprehensive as possible. If a box becomes 50% smaller, you might save 10-cents on materials but save $10 in shipping. If more fit in the shipper, you might lower per unit sterilization and logistics costs. If you make a change that forces revalidation, consider improving each impacted component. This is the time to maximize the upside. Make sure you capture all your current and anticipated costs.

By using less material, there will be less to incinerate which is cheaper for the customer. “It’s important to make the solid business case to stakeholders as to why a change needs to be made,” he explained.

Though much of the focus is on the end user, Barnell said not to overlook packaging operations. There is a cost associated with every step in the packout, and the more error-free the better. Optimize the work steps wherever possible. You can ask an operator what improvements they want but they might not know. Knowing what you want is tied to knowing what is possible. It is much better to give operators a prototype package and ask if it is better. If you have the chance, observe and time them—counting the seconds—which will allow you to calculate the change in per-unit costs.

“We developed assembly assistance tools and brought them to packout technicians. By allowing them to experiment, we projected the packout time,” Barnell explained. “We became partners in the new design. Even if you give them something that isn’t just right, you gain insight. There’s cross-pollination. Stakeholders always tells you what they don’t like, which gives you the opportunity to fix it.”

Considerations for the future

Barnell advised those developing packaging to:

-

Make your efforts count by identifying and pursuing features, material and processes that create significant impact. “Downgauging a tray may save 25 cents, is it worth it to spend $100,000 revalidating? Restricted resources could have gone to other improvements,” he noted.

-

Size really matters, as it creates a multitude of cost reduction and sustainability opportunities. “Think about all the empty space in a typical package. By making the package smaller, the amount of shipping cost you save is dramatic,” he said. “Less material means lower component cost and less to throw away.”

-

Some may have ideas to make a package look more Apple-like, with bigger packaging and less sustainable materials. But Barnell recommended choosing smaller, more sustainable materials. “Create a story around it being sustainable. The shipping cost goes down, and balances the potentially more expensive but Earth-friendly materials.”

-

Be organized and comprehensive. “Cost savings starts with visits to the users on the assembly line, distribution center and clinic or hospital. Without the knowledge you gain here, the only target you have is reducing materials cost. Adding functionality reduces cost within for every stakeholder function, many times greater than what you would achieve focusing on materials alone.”

-

Packaging can be more than a sterile barrier and a place for labels. “Commit yourself to not only understanding what each stakeholder does but also what they could do better,” he said. “Figure out how your packaging can help and this becomes real opportunity to bring added value.”

Sidebar: Real-world Packaging

Unlike the passive packaging that we see as consumers, medical packaging and labeling serves as a tool for people in the chain that ultimately delivers care to a patient. For some, our work brings information that elevates the safety of the device — such as an orientation arrow for the sterilization technician or balloon inflation chart to the cardiologist. For others, our designs complete an actual task —like the audible sound that the pack out worker hears when the device is properly locked into the tray or staging the components that will be assembled by the surgical team. It is this difference that not only creates essentially unlimited opportunities to improve our packaging and labels, but also makes our work incredibly rewarding.