While the healthcare packaging and medical device communities have been exempted from certain material regulations, recent discussions have highlighted the need for companies to prepare for changing laws, especially those pertaining to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly referred to as "forever chemicals." These chemicals do not readily breakdown in the body or environment and have been linked in studies to endocrine disruption, certain cancers, and more.

During a session at the[PACK]out in May 2023, experts from Boston Scientific and Amcor shared insights on the global regulatory landscape and its implications for healthcare brand owners. To start, Alex Bowman, R&D manager at Amcor, emphasized the importance of staying informed and prepared for regulatory changes that will impact the life science packaging community, underscoring the need for companies to anticipate and adapt to these shifts.

PFAS uses in healthcare packaging

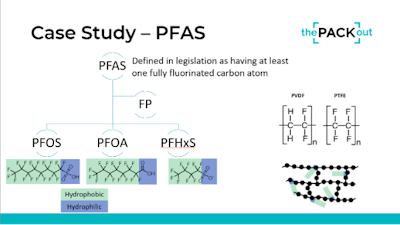

PFAS, which encompasses a broad range of chemicals used for their hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties, have come under scrutiny due to their persistence in the environment and potential health impacts. Haley Gorr, PhD, an engineer and global product steward from Boston Scientific, said, “What's really important to understand is how PFAS is defined in the legislation. PFAS is really an umbrella term including PFOS, PFOA, PFHS—they're very similar. In the legislation, they've been shifting towards a very holistic definition of PFAS. There's not a lot of opportunity to differentiate between those different types of molecules. They're saying, ‘If you have one fully fluorinated carbon atom, then you're in scope.’ And that’s where everyone’s landing whether EU, U.S., etc.”

Gorr said that while their presentation wasn’t about debating the merits of these chemicals, it’s important to understand that there is a difference between molecular PFAS and polymerized PFAS, noting that the latter, known as fluoropolymers or FPs, are non-toxic due to their stable, locked-in structure.

Haley Gorr/Alex Bowman via the[PACK]out

Haley Gorr/Alex Bowman via the[PACK]out

“Fluorinated polymers have really helpful properties. We like them because they are biologically inert, they are hydrophobic, and they contribute lubricity to our products because the water sits on top of those materials [due to the hydrophobic fluorinated carbon atoms],” she said (see image above). She explained that PFAS is generally used in medical devices to add lubricity and reduce friction on some catheters, wires, and implants. Another common application is to cover electrical wires that come into contact with tissue, such as the lead wires of some defibrillators and pacemakers. There are limited, if any, alternative materials for these complex applications at present.

There are, however, some traditional PTFE applications with alternative materials. Gorr explained that PTFE may be included in glossy carton coatings to prevent sticking. PTFE-free carton coatings are now widely available. ![Haley Gorr talks polymer chemistry and regulations at the[PACK]out.](https://img.healthcarepackaging.com/files/base/pmmi/all/image/2024/01/Haley_Gorr_at_thePACKout.65aeffe3d8fd9.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) Haley Gorr talks polymer chemistry and regulations at the[PACK]out.

Haley Gorr talks polymer chemistry and regulations at the[PACK]out.

Bowman explained why converters use materials that fall under the PFAS umbrella in their films as processing aids. “Typically, linear low densities [LLDPE] and polypropylene are the kinds of materials that can use aids in processing. There's a stick-slip phenomenon when these polymers are extruding through a die interface and these fluoropolymers and fluoroelastomers reduce that friction against the interface. So it's basically eliminating things like melt fracture and orange peel and gives a nice clear film so you can see what’s inside your package.”

Market forces and indirect effects

The implications of PFAS bans extend beyond the immediate concerns of compliance. Pharmaceutical and medical device brands may only represent a small portion of a converter’s total business. As converters comply with regulations for food and CPG packaging, eventually it may not make economic sense to carry PFAS-containing materials solely for life science brands.

“We're seeing some of those impacts in the regulations in food packaging that are driving a lot of action right now. We're actively changing out of PFAS-containing materials to not-intentionally-added PFAS materials, including resins and additives that we're buying from our suppliers, and then upstream even further to those chemical manufacturers making the fluoropolymers and fluroelastomers that we use as processing aids,” said Bowman. “Think about what the demand change feels like to the chemical manufacturers and resin and additive producers. They're seeing a major shift away from one type of material.” ![Alex Bowman discusses PFAS at the[PACK]out.](https://img.healthcarepackaging.com/files/base/pmmi/all/image/2024/01/Alex_Bowman_at_thePACKout.65aeff86d668b.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) Alex Bowman discusses PFAS at the[PACK]out.

Alex Bowman discusses PFAS at the[PACK]out.

For now, Bowman reckons converters will continue to support healthcare customers with the existing materials. “But I don't expect it to be that way forever. Eventually, you can see the demand start to shift and it probably becomes unprofitable and unlikely that they're going to continue to support what's a pretty small consumer in terms of all of the plastics in the world,” he added. “We're able to avoid some of these regulations because we're in our own regulated markets. But some of these things are going to come at you from further up the supply chain than even [suppliers] can control.”

Legislation: U.S. and Abroad

The conversation touched on legislative actions at the state level in the U.S., with Vermont being the first to enact a ban on PFAS-containing food packaging that went into effect July 1, 2023. This move is expected to have a ripple effect across the industry. Bowman pointed out that while Vermont may be a small state, it’s “the first one, and there are many states coming down the pipeline with even more PFAS bans."

Maine’s PFAS-reporting law requires disclosure of certain materials in products. While packaging is currently exempt, according to a local news report, manufacturers are grappling with the difficulty of identifying PFAS in their products and supply chains. Bowman noted that some MDMs’ [medical device manufacturers’] regulatory teams may already be working on how to report to remain compliant in Maine. That regulation also has a PFAS ban built in for 2030.

In California, the AB 1200 regulation targets fiber-based food-packing such as food wrappers and microwave popcorn that use PFAS for grease resistance.

Outside of the U.S., new regulations include a mineral oil ban in France for food packaging, a PVC food packaging ban in Taiwan, and mandatory packaging reporting in Singapore.

Additionally, Gorr highlighted the proposed EU PPWR, the Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation, evolving from the directive (PPWD). “This [regulation] is still the same content as the [directive]. You're still required to report on what's in your packaging waste and be accountable for it,” she said, which ties into extended producer responsibility and environmentally preferred purchasing (EPP) programs. “It's not just regulations that we need to care about, it's also what our customers are requiring of us. It's a different type of requirement, but still a requirement. If they're asking you for recycled content, I feel that we are obligated to supply that to them, if possible,” Gorr said.

Looking ahead, the life science packaging community must prepare for the possibility that medical device packaging and devices themselves may not remain exempt from these regulations indefinitely. Gorr, who owns the advocacy gap assessments for the REACH regulations at Boston Scientific, pointed out that while medical devices might currently be shielded from certain bans, the industry must remain vigilant and proactive in its approach to regulatory compliance. "Medical devices are not going to be exempted forever," she cautioned, suggesting that the industry should be proactive in engaging with legislators and educating them on the potential socioeconomic impacts of proposed bans.

What’s next?

As the regulatory environment continues to evolve, the industry faces the challenge of balancing compliance with innovation and sustainability. The session concluded with a forward-looking question posed to the audience: "What do you think the next PFAS will be?" As Bowman and Gorr highlighted, PFAS is certainly not the last material of concern that will either be banned or discussed in the media as an environmental or human health risk. Responses varied, indicating a wide range of concerns about potential future regulations on materials such as colorants, additives including titanium dioxide, BPA, PVC, styrenes, and nanoparticulates.

Understanding, adapting to, and anticipating the regulatory landscape will be critical to maintaining compliance and ensuring the continued viability of healthcare products and processes.

Takeaways:

- The regulatory concepts of materials of concern, packaging waste, and extended producer responsibility have become blended. Gorr explained that in the past, there may have been material regulations for the chemical producers specifically, but now the focus is on overall environmental concern. The PFAS umbrella is receiving regulatory attention because of human health concerns. “It's a forever chemical in our bodies and in the environment,” she said. The legislation will continue to evolve on the rationale that environmental health is just as important as human health.

- Life science packaging and medical devices will not be exempted from PFAS regulations forever. These changes and impacts will be felt throughout the supply chain. The healthcare community can learn lessons from the food and consumer industries that are experiencing and adapting to these changes at a much faster pace, said Bowman.

- Suppliers should be testing their materials, so lean on your supplier letters for REACH compliance. Gorr said that the REACH regulation specifies you do not need to prove the absence of a chemical, while for MDR compliance, you do. Bowman also noted that anyone can test their materials—even consumers—since it only takes as little as 10 grams of film to submit for testing.

- It’s important for regulatory and packaging professionals to collaborate with value chain partners early on. An MDM may be concerned about a specific package or rollstock, but Bowman advised attendees to look at their current portfolio and have a broader discussion about how regulations might impact it. Bans may not directly impact an MDM’s product, but Gorr said there may be PFAS used somewhere upstream or in non-product contacting applications so it’s important to consider how operations and suppliers are affected.