The WHO has a significant presence in emerging countries and continues to tackle challenges associated with bringing healthcare and vaccinations to remote areas of the world.

Geoffrey Glauser is a subject matter expert in support of the Manufacturing, Facilities, and Engineering Division of the Biomedical Advancement Research Development Authority (BARDA) in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) within Health and Human Services (HHS). Recently, he played a key role working with the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in Sierra Leone on a Phase 2-3 clinical trial for the Ebola vaccine.

At this week’s IQPC 14th Cold Chain - GDP & Temperature Management Logistics Global Forum in Boston, he explained that what he and the CDC accomplished in the area of Ebola prevention was a “trial by fire” in Sub-Saharan Africa, learning as they went to complete the clinical trial under extreme conditions.

“The task [people] have is certainly not simple,” Glauser noted. People must bring in resources and standards, and educate. The basics of water and electricity are limited. “It’s not enough to just have cell phone service.”

There were power outages and minimal grid cover, and only 12 percent of roads were paved. He explained that they rose to the challenge, never losing a dose of the -80°C vaccination despite the lack of dry ice.

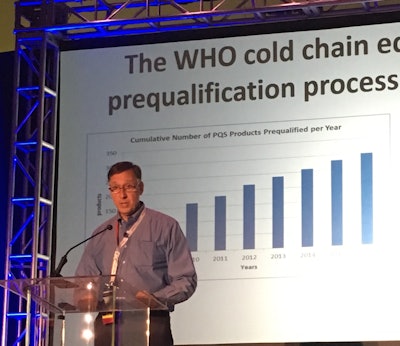

Glauser outlined the WHO’s equipment prequalification process and implementation strategies that address the unique challenges in emerging countries. He recommended that companies involved in cold chain operations in emerging markets consider the following:

-

Solar panels on cold rooms can feed electricity into the unit when there is limited grid power to handle the temperature control you want (-20°C or 2-8°C). The panels have to be cleaned to prevent dust accumulation.

-

Climate conditions may mean that winter weather may not take place, but there may be rainy seasons without sun, so you need to ensure there is backup energy. You have to ask yourself what power you need when the sun is not shining, such as battery backup and emergency generators. He noted, “It’s hard to maintain the continuity of power.”

-

You have to pay attention to electrical continuity, liquids inside batteries, and test batteries. These are critical functions for cold chain.

-

The quality of 220-volt power in some remote areas can be dodgy at best. The unit may plug in and work initially, but if electrical phases are out of sync, you may burn up a compressor in a year. Some equipment has voltage regulation built in. Glauser said this is part of the qualification, and added, “I would demand voltage regulation if there’s a questionable electrical grid.”

-

Backup generators can be a lifesaver, but there is an issue about keeping them well maintained. Also, liquid fuel (such as gasoline or jet fuel) is internationally priced, and many emerging economies don’t have the money. Glauser noted that in the field, he saw 100 small motorcycles donated by Japan, which could have valuable in delivering medical products. But they were sitting and gathering dust, because the area did not have a budget for gasoline. Continuity of fuel is not a given.

-

It may be wise to back up your backups. He said he used a three-layer electrical system: a generator, solar power and a backup generator.

-

In situations where you have backup power supply, consider whether you will use an auto switchover or perform manual switching.

-

If a freezer does not have a temperature recorder, you will need to attach an independent recorder. You must take a temperature reading of each unit at least twice a day, and it is preferable to monitor every 15 minutes to ensure the vaccines are viable.

-

Glauser noted that while there are often local equipment manufacturers in the U.S. and Europe, the WHO doesn’t have the luxury of a -20°C freezer supplier in Nigeria or Togo. You must consider transportation costs, which can be almost the same price as the unit itself.

-

Also consider the difference between the standard operating conditions of the equipment and the reality of the situation. For example, -20°C freezers need a certain ambient temperature to operate satisfactorily. If they are used in Sub-Saharan Africa, they will have a shorter lifetime if they are operating in heat without preconditioning to a 20-22°C environment.

-

Ensure equipment manufacturers understand where units will be used. There are manufacturers that offer freezers that can operate in the heat, with compressors and mechanical systems that can handle those temperatures. Glauser noted, “We don’t need that in the U.S. because [our freezers] are usually in temperature controlled environments,” such as factories or labs.

-

Follow up and provide feedback to technicians about satisfactory or unsatisfactory freezer performance.

-

Field validation must be performed to confirm that the system works once installed, and that it can be utilized for long term storage.

It’s extremely important that you do not overlook human factors. The local ministry of health must be involved from the start—they have their own requirements and standards, as do other aid organizations like UNICEF. You may need to keep the local leader(s) happy, and will ultimately teach locals how to perform vaccine storage and equipment maintenance. Glauser said that the local leaders and healthcare providers want to be in charge as much as anybody, and it’s our job to make sure they are educated and self-sustaining.

Public health education is also a critical component in emerging countries. Ebola is more difficult to transmit than many think, as it requires contact. Much of limiting the spread of the disease comes down to education, and Glauser urged attended to view and share the massive number of educational activities related to public health at WHO.