Patients and consumers are rightfully worried about what happens to their data once it’s in a company’s hands. From major phone glitches to a smart thermometer company selling data to sterile wipe manufacturers, there’s a lot of uncertainty that comes with the territory of using any smart device.

At Pharmapack 2019, Alex Driver, Senior Consultant at UK-Based design and development firm Team Consulting, said that despite the concerns, people still use phones and other connected devices daily because (obviously) there’s a value that far exceeds the perceived cons.

The barriers to going connected with medical devices include negative attitudes toward sharing data, technical complexity and potential wastefulness.

But for many devices, there may be enough pros to forge on with connecting. These opportunities include:

-

Improving patient competence

-

Helping patient engagement

-

Communicating therapy benefits

-

Adherence support

-

Disease self-management

-

Differentiating among competition

-

Building confidence in clinical trial results

-

Learning about patient behavior

Driver was very clear in his message: “To connect or not to connect” isn’t the right question. Drug and device manufacturers should really be asking themselves, “What problem am I trying to solve?”

There has to be value (such as the opportunities listed above) that meet patient, healthcare provider, payer and regulatory needs.

He discussed a potential approach for deciding to go connected. There are three categories of solutions:

-

Dumb: Everything is unconnected. The patient deals with their doctor through face-to-face interactions, email or text.

-

Smart: The device may prompt the user, but data remains on the device, visible only to the user.

-

Connected: Data is shared with the cloud either continuously or by intermittent download. Data is available to those with permission.

For Team Consulting, the company gathers a multi-disciplinary team and works through a matrix with opportunities across the top and categories of devices on the Y-axis. They populate the matrix, noting how each type of device could meet the benefit.

To bolster patient adherence for example, a dumb device may receive a packaging redesign so that the package steps the user through the package. A smart device may prompt the user through the use of an LCD screen, while a connected device could share data with the healthcare provider so that the user is prompted with an email or phone call.

For each part of the matrix, they ask how well a solution meets the particular stakeholder need, noting risks or technology constraints. They ask if the outcome could be achieved with a dumb solution. Ultimately, the best answer may be a suite of solutions and not one single design update or choice to connect.

Connecting an existing device

More often than not, Driver said you’ll be modifying an existing device. If this is the case, try not to impact device functionality to avoid the need to reverify and revalidate. For example, if you put something in an inhaler’s air path to sense inhalation, it might inhibit the air flow. You could place a microphone on the outside of the device to listen for a change in tone, maintaining the air path as it was validated.

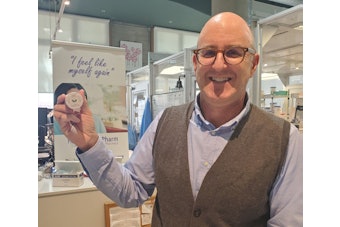

How do you integrate connectivity? You may be able create a sleeve for the device so that existing devices (and manufacturing lines) remain as is. The benefit is that a sleeve is reusable and cuts down on the cost of treatment, but you are relying on the user to add it on. You have to ask yourself what the user is getting in return for that added step. Value-added functions for the patient may include easy communication with phone/app for convenience or smart reordering.

You may also consider a bolt-on in the manufacturing process, removing a piece of casing. In this case, you are not asking the user to perform the extra step, but every time they throw out the device, they throw out the electronics with it.

If the connectivity is fully Integrated (i.e. you change the moldings), the risk is that you likely have to revalidate your product and production line.

Driver offered attendees several other tips including:

-

Create a quick and dirty prototype, the earlier the better. Companies such as Nordic Semiconductors, Texas Instruments and Diolan make development boards which can be used for quick prototyping.

-

When testing early, get feedback from a set of stakeholders (not only the users).

-

Deciding what to sense is really key—more data means more storage space, a greater power budget and greater cost.

-

Be selective about what you communicate to the user. For example, an Apple watch offers a very pared down view of activity for the day. There’s a lot of data in the background, but the user is seeing a simple and appealing set of three colorful circles and trying to close the gap (see image).

-

Don’t overlook voice control. This feature is quite prevalent in the consumer electronics industry for good reason. As Driver noted, “There’s quite a lot of opportunity there. You don’t have to interact with a user interface. You ask a question more or less when you think of it, so this may reduce cognitive load for the user.”

-

Right now, voice commands are mostly about making a request. But the industry may be moving toward systems providing the user with prompts.

-

A successful app or device will likely strike a balance of functionality and utility (not just novelty), and will not make the user do things they don’t want to do.

Key takeaway

The human factor cannot be overlooked. If the user is losing privacy to use a connected device, they need some other benefit to motivate them to engage with the system. “And feeling better might not be enough,” Driver said. “We have to shift patient behavior with good design.”

Editor's note: For a roundup of all of Healthcare Packaging’s coverage from Pharmapack, click here.>>