If it’s here, it’s got to comply. U.S. laws and regulations apply to both products made here and to those that are imported from other countries.

So if you’re going to have an international economy—and we do—and products and packages are going to be imported into the U.S. from other countries—and they are—then it matters a great deal to U.S. businesses and regulators how foreign manufacturers do what they do. To help assure they do it right, you can wait for the products to get here and try to check them out when they do. Or you can put systems in place that will help make sure those products get made right in the first place, by educating foreign manufacturers about FDA expectations and requirements.

Well, checking every imported shipment is tough—FDA has reported FDA-regulated products were the subject of 24 million shipments in fiscal 2011. FDA has a presence in foreign countries and actually inspects and interacts with some foreign manufacturers.

But it’s nice if the foreign governments join in, regulating and overseeing and educating in their own countries to get companies up-to-speed on the kinds of standards and requirements we like here in the U.S. That’s especially true of an ever-larger player on the world stage, China. Despite all its impressive recent emergence in a variety of industries, some Chinese companies have been the subject of a series of scandals and product problems in recent years.

The Chinese government recently announced a reorganization and new powers for their regulators that could affect many important FDA-regulated products. The China Food and Drug Administration, or CFDA, emerged from changes to the State Food and Drug Administration, and is now a “ministry”—something like a cabinet-level department in the U.S.—with more powers over the safety of the domestic food supply, which had previously been housed in three other agencies.

If you trace the history of FDA’s powers and jurisdiction, there’s a common theme of changes and expansions to its powers following one or another public health disaster. It’s similar with China. FDA notes that infant formula tainted with melamine sickened or killed many thousands of Chinese babies in 2008, and problems with the blood thinner Heparin, as well as pet food, toothpaste, seafood and other products, which affected consumers here as well as there, helped inspire the changes in China.

So now here’s the CFDA, with powers over food including dietary supplements, drugs, and medical devices. Its focus will be on assuring the safety and compliance of Chinese domestic businesses, but because so many of them supply U.S. businesses, that could indirectly help us here. It remains to be seen what if any substantive changes will come out of this reorganization in terms of requirements for foods, drugs, and other products.

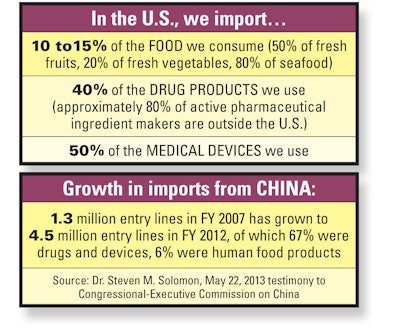

Many products sold here, or parts of them, are made elsewhere. According to FDA’s associate commissioner for global operations and policy, Dr. Steven M. Solomon, “Today, FDA-regulated products originate from more than 200 countries and territories and pass through more than 300 U.S. ports.” He told a Congressional-Executive Commission on China in May that “The number of FDA-regulated shipments has more than tripled from 8 million import entry lines per year a decade ago to 28 million entry lines” in fiscal 2012, and are expected to reach 34 million in fiscal 2013.

FDA has long had a complex and multifaceted approach to the problem of assuring that products getting here comply with our laws and regulations. They literally do send people to inspect factories in foreign countries, but they also keep up communications with regulators from other countries and even overseas businesses and international organizations. Old fashioned problems like poorly made drugs, or improperly labeled foods, and more new-fangled problems like counterfeit drugs, all can be addressed via such cooperation.

In addition to having international offices and 12 foreign posts in 9 countries, FDA examines imports. They can’t physically examine all the millions of imported shipments, but they can screen them electronically using an “automated risk-based system to determine if shipments meet identified criteria for physical examination or other review.” Called PREDICT, for Predictive Risk-based Evaluation for Dynamic Import Compliance Targeting, it blends information from multiple sources, like past experience with that type of product, results of inspections, information from other governments, and even intelligence data and weather information. Solomon explains, “This system allows FDA to focus its resources on those imports that are most likely to pose a danger, while at the same time facilitating entry of low-risk products.”

The hope is that China’s new higher-profile, more empowered agency will help prevent the kinds of problems seen in the past. In the meantime, FDA will continue its efforts here, there and everywhere to assure the safety and quality of products reaching the U.S.