It is hard to pick up a magazine or news publication and not see one or more stories about health and wellness that details a beneficial or questionable dietary ingredient. Web news sites highlight articles about vitamins, minerals, ingredients, herbs, or fruit that tout a health benefit. It is also hard not see another article that states that an ingredient or vitamin has no effect or is detrimental to some other health-related condition.

There is no shortage of information on anything that grows or is assimilated by the body stating the benefits or the shortcomings of the products. It's a confusing state of affairs that requires readers/consumers to weigh the evidence and make informed choices about ways to improve their health naturally. Such is the state of research and understanding relating to the hard-to-define wellness space found between food, dietary supplements, and pharmaceuticals.

For Healthcare Packaging readers, how to package these products is an additional question. Before one can decide what is required to package this group of products, one must understand what they are, how they are defined and regulated, and how they must be labeled.

The terms Nutraceutical, Dietary Supplement, and Medical Food all carry very different definitions and different expectations, which are blurred in the news and in everyday use by consumers, which makes the terms seem interchangeable or makes the products appear to be the same. This creates problems for consumers and requires manufacturers to know what is required to properly categorize and label, and safely manufacture any of these products.

Packaging for drugs, dietary supplements, and medical foods is defined in different parts of the FDA's CGMP (Current Good Manufacturing Practice) guidelines for the products and is further defined in the food regulations. Packaging and labeling of each of these products must follow guidelines issued by the FDA. For supplements, these regulations were recently revised and issued in June 2007 under 21 CFR Part 111, while regulations for drugs are found in 21 CFR 110.

Nutraceutical is a term coined in 1989 by Dr. Stephen DeFelice. The term is commonly used for marketing a wide array of products, but it has no regulatory definition. Dr. DeFelice defined Nutraceutical as, “a food (or part of a food) that provides medical or health benefits including prevention and/or treatment of a disease.” The main problem with this definition is that it encroaches on the FDA definition of a drug (A treatment, prevention, or cure for a specific disease or condition is considered a drug, and because it [the nutraceutical] was not approved by the FDA for treatment of the disease, an illegal drug). It also overlaps with the definition of a dietary supplement defined by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994, which states a dietary ingredient must be one or a combination of the following substances:

• A vitamin

• A mineral

• An herb or botanical

• An Amino acid

• A dietary substance for use by humans to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake (e.g., enzymes or tissues from organs or glands), or

• A concentrate, metabolite, constituent, or extract

The DSHEA act also defines a “new dietary ingredient” as something that meets the above definition of a “dietary ingredient” but was not sold in the U.S. in a product used as a dietary supplement before October 15, 1994. The responsibility to prove that a new ingredient is safe and was not sold before 1994 falls on the product manufacturer. Without trying to complicate this further, the definition of GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) ingredients and the items on the list of GRAS substances can also overlap with this.

Medical foods

Medical foods have had an interesting history. The FDA reclassified these products in 1972 from drugs to food but because a large number of questions about the term “Medical food” continued, they issued a guidance that helps distinguish between medical foods, drugs, and dietary supplements with clarification of the regulatory requirements surrounding medical foods.

The term medical food is defined by the government as “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” (21 U.S.C. 360ee (b) (3) section 5(b) and later was incorporated by reference into the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (P.L. 101-535) of 1990). Medical foods are a narrow segment of the food marketplace. They must meet the requirements of 21 CFR 101.9 (j) (8) for nutrition (food) exemption purposes. The criteria are:

• It is a specifically formulated or processed product (as opposed to a naturally occurring food or food constituent) for the partial or exclusive feeding of a patient by enteral feeding tube or oral intake.

• It is intended for the dietary management of a patient who has limited or impaired capacity to ingest, digest, absorb, or metabolize ordinary foods or specific nutrients. These patients have medically determined nutrient requirements that can't be achieved or managed by the modification of a normal diet.

• It is targeted to provide specific nutritional support modified for the management of unique nutrient needs that result from a specific disease or condition determined by the examination of a physician.

• It is intended to be used under medical supervision.

• It only applies to patients receiving active and ongoing medical care and requires instructions as to its use.

In order to understand what a product is and what it isn't is important because it provides the framework needed to understand the regulations that surround what the product is or is not and what is expected in terms of manufacturing, labeling, and marketing of the product.

What does all this mean for each of these products? Let's start by providing what the government requires for each of the defined terms and then showing how the term nutraceutical can be applied to any and all of the products. It is also worth touching on ordinary foods that can also be called nutraceuticals.

Dietary supplements

For dietary supplements regulated under DSHEA, a firm is responsible for testing and proving the dietary supplement it manufactures or distributes is safe and that the claims made about the product can be substantiated with adequate evidence to show they are not false or misleading. This means that dietary supplements are not subject to submission testing and approval by the FDA prior to their introduction. The only exception to this is for the case of a “New Dietary Ingredient,” defined earlier. Manufacturers are required to register themselves pursuant to the Bioterrorism Act with the FDA prior to producing or selling supplements. CGMPs for dietary supplements were published in June 2007, and these regulations deal with the identity, purity, quality, strength, and composition of the products.

Adequate evidence, noted above, typically means clinical trials or studies that are large enough and statistically meaningful to demonstrate the benefit of the supplement. Unfortunately, to develop trials large enough to prove these points is extremely costly, and many of the trials, whether performed by the manufacturer or by universities or other groups interested in the science of nutrition, produce results that are difficult at times to summarize with strong conclusions.

Before you think this should be easy, remember, people in any study group can have or not have many different levels of nutrition from their everyday diet, and increasing or changing a component of the diet may or may not produce a simple-to-understand result. When one does studies on a new drug, only one outcome using a very carefully screened group of patients is used in many of the trials, making the conclusions a little easier to reach.

Another way to understand some of the complexity is to think of drug interactions. No one studies drug interactions to any large degree. For a patient taking multiple drugs, it is up to the individual patient and her or his physician to monitor what is going on and whether she or he is receiving the multiple benefits of each of the drugs. For both supplements and drugs, the placebo effect also plays a role in the overall benefit. Reputable companies manufacturing, distributing, and selling dietary supplements typically rely on multiple studies or larger definitive studies that provide a good scientific basis for the claims they make.

The FDA publishes a commentary regarding claims that can be made for dietary supplements, which provides an overview of the claims that can or cannot be made. If a product claims to be a treatment, prevention, or cure for a specific disease or condition, it would be considered and regulated as a drug.

The safety of dietary supplements comes under the jurisdiction of the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) because they are in final analysis foods. This organization is charged with obtaining evidence by monitoring the marketplace. They obtain information from consumer and trade complaints, reporting of adverse events for products (a log detailing all adverse events is required by law for a manufacturer or distributor of supplements), and in unusual instances, their own laboratory analysis of the products.

Regulations, label claims, and confusion

One confusing aspect surrounding the labeling of dietary supplements is the DSHEA-required disclaimer statement, “This statement has not been evaluated by the FDA. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” This statement is required when a manufacturer makes a structure/function claim on a dietary supplement label. These claims generally describe the role of a nutrient or dietary ingredient intended to affect the structure or function of the body. The manufacturer is responsible for making sure a claim of this type can be proved. They are not approved by the FDA. In contrast, the FDA reviews and approves labeling on a drug. The disclaimer required under DSHEA tells the consumer that the FDA has not evaluated or approved the claim. The “…diagnose, treat, cure or prevent a disease…” portion of the statement tells the consumer the product is not a drug.

Another area of confusion in the marketplace over dietary supplements, the terms nutraceutical and medical food come from how advertisements for dietary supplements are regulated. Another agency, the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) is responsible for regulating advertising and infomercials about dietary supplements and most other products sold to consumers. The law and regulations for the FTC are different from those for the FDA. The two agencies work closely together many times on products and questions about these products, but the final application of specific requirements is different for the two agencies.

How a medical food is defined and regulated is different from a dietary supplement. The term medical food is defined as part of the Orphan Drug Act in section 5 (b) 921 U.S.C. 360ee (b) (3) as “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements based on recognized scientific principals are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA advises that it considers this statutory definition of medical foods to limit and narrowly constrain the types of products that fit within this category of food.

Without going into all the other details and requirements for labeling of medical foods, the easiest thing to keep in mind for these products is that they can only be used to treat a disease condition. They do not fall into the broader categories of foods for special dietary use or foods making health claims. They can only be used for meeting the special nutritional requirements posed by a disease, and they must be prescribed and administered under medical (physician) supervision. The term medical food does not apply to all foods fed to sick patients.

The FDA does not require a medical food to undergo premarket review or approval. Individual medical food products do not require registration with the FDA. For more information on all of these questions please refer to the FDA's Guidance for Industry: Frequently Asked Questions About Medical Foods (www.cfsan.fda.gov/guidance.html)

Question, and weigh facts

After reading all of this, I'm sure many of you are surprised about how complicated this subject really is. Something easy and simple, a food that benefits a person with many therapeutic properties like a drug appears to be a “no brainer” to understand. It is only when you start to ask questions about what it does, how it does it, and how do you prove it that the whole array of definitions and regulations suddenly make sense.

Dr. DeFelice really started something with the term nutraceutical. He wanted to convey how naturally occurring foods and the management of nutrition supplemented by other naturally occurring products could convey healthful and therapeutic benefits to people. Unfortunately a simple idea, treating disease with food, can be very difficult to understand when viewed in a practical, fact-based, clinically researched analysis. When a person wants to treat a problem with products occurring naturally or when someone wants to avoid traditional drugs for treatment of a disease or condition, hard study is required of many facts and opinions available before one can reach a conclusion about what is best for them.

Hopefully after reading this you will want to carefully weigh the facts about anything you are considering for improving your health or for treating a natural condition with “high potency” food as something that requires diligence and understanding to uncover the ones that make a difference in your everyday life.

-By Edward J. Bauer

Edward J. Bauer is Senior Director, Product and Package Innovation and Development for GNC, Pittsburgh, PA, and 2006 inductee into the Packaging Hall of Fame.

__________________________________________

Definitions:

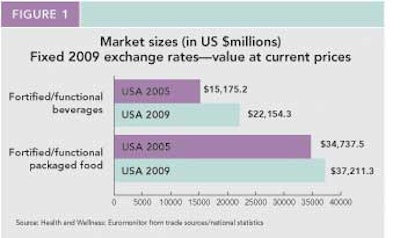

Fortified/functional packaged food: This category includes packaged food to which health ingredients have been added. Fortified/functional packaged food provides health benefits beyond its nutritional value and/or the level of added ingredients wouldn't normally be found in that food. To merit inclusion in this category, the defining criterion here is that the product must have been actively fortified/enhanced during production. As such, inherently healthy products such as naturally healthy soymilk are only included under “functional” if additional functional ingredients (e.g., omega-3) have been added. To be included, the health benefit needs to form part of positioning/marketing of the product. There is one exception to the inclusion of fortified products in this category: Products to which vitamins have been added to replace vitamins lost during processing are excluded. These products would not typically be positioned on the basis of containing added nutrients.

Fortified/functional beverages: This category includes fortified/functional soft and hot drinks. When identifying fortified/functional products, we focus on products to which health ingredients (typically those with health claims) have been added. Fortified/functional beverages provide health benefits beyond their nutritional value and/or the level of added ingredients wouldn't normally be found in that product. To merit inclusion in this category, the defining criterion here is that the product must have been actively fortified/enhanced during production. As such, inherently healthy products such as 100% fruit/vegetable juices are only included under “fortified/functional” if additional health ingredients (e.g. calcium, omega-3) have been added. To be included, the health benefit needs to form part of positioning/marketing of the product. One exception: Products to which vitamins have been added to replace vitamins lost during processing are excluded. These products would not typically be positioned on the basis of containing added nutrients.

There is no shortage of information on anything that grows or is assimilated by the body stating the benefits or the shortcomings of the products. It's a confusing state of affairs that requires readers/consumers to weigh the evidence and make informed choices about ways to improve their health naturally. Such is the state of research and understanding relating to the hard-to-define wellness space found between food, dietary supplements, and pharmaceuticals.

For Healthcare Packaging readers, how to package these products is an additional question. Before one can decide what is required to package this group of products, one must understand what they are, how they are defined and regulated, and how they must be labeled.

The terms Nutraceutical, Dietary Supplement, and Medical Food all carry very different definitions and different expectations, which are blurred in the news and in everyday use by consumers, which makes the terms seem interchangeable or makes the products appear to be the same. This creates problems for consumers and requires manufacturers to know what is required to properly categorize and label, and safely manufacture any of these products.

Packaging for drugs, dietary supplements, and medical foods is defined in different parts of the FDA's CGMP (Current Good Manufacturing Practice) guidelines for the products and is further defined in the food regulations. Packaging and labeling of each of these products must follow guidelines issued by the FDA. For supplements, these regulations were recently revised and issued in June 2007 under 21 CFR Part 111, while regulations for drugs are found in 21 CFR 110.

Nutraceutical is a term coined in 1989 by Dr. Stephen DeFelice. The term is commonly used for marketing a wide array of products, but it has no regulatory definition. Dr. DeFelice defined Nutraceutical as, “a food (or part of a food) that provides medical or health benefits including prevention and/or treatment of a disease.” The main problem with this definition is that it encroaches on the FDA definition of a drug (A treatment, prevention, or cure for a specific disease or condition is considered a drug, and because it [the nutraceutical] was not approved by the FDA for treatment of the disease, an illegal drug). It also overlaps with the definition of a dietary supplement defined by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994, which states a dietary ingredient must be one or a combination of the following substances:

• A vitamin

• A mineral

• An herb or botanical

• An Amino acid

• A dietary substance for use by humans to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake (e.g., enzymes or tissues from organs or glands), or

• A concentrate, metabolite, constituent, or extract

The DSHEA act also defines a “new dietary ingredient” as something that meets the above definition of a “dietary ingredient” but was not sold in the U.S. in a product used as a dietary supplement before October 15, 1994. The responsibility to prove that a new ingredient is safe and was not sold before 1994 falls on the product manufacturer. Without trying to complicate this further, the definition of GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) ingredients and the items on the list of GRAS substances can also overlap with this.

Medical foods

Medical foods have had an interesting history. The FDA reclassified these products in 1972 from drugs to food but because a large number of questions about the term “Medical food” continued, they issued a guidance that helps distinguish between medical foods, drugs, and dietary supplements with clarification of the regulatory requirements surrounding medical foods.

The term medical food is defined by the government as “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” (21 U.S.C. 360ee (b) (3) section 5(b) and later was incorporated by reference into the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (P.L. 101-535) of 1990). Medical foods are a narrow segment of the food marketplace. They must meet the requirements of 21 CFR 101.9 (j) (8) for nutrition (food) exemption purposes. The criteria are:

• It is a specifically formulated or processed product (as opposed to a naturally occurring food or food constituent) for the partial or exclusive feeding of a patient by enteral feeding tube or oral intake.

• It is intended for the dietary management of a patient who has limited or impaired capacity to ingest, digest, absorb, or metabolize ordinary foods or specific nutrients. These patients have medically determined nutrient requirements that can't be achieved or managed by the modification of a normal diet.

• It is targeted to provide specific nutritional support modified for the management of unique nutrient needs that result from a specific disease or condition determined by the examination of a physician.

• It is intended to be used under medical supervision.

• It only applies to patients receiving active and ongoing medical care and requires instructions as to its use.

In order to understand what a product is and what it isn't is important because it provides the framework needed to understand the regulations that surround what the product is or is not and what is expected in terms of manufacturing, labeling, and marketing of the product.

What does all this mean for each of these products? Let's start by providing what the government requires for each of the defined terms and then showing how the term nutraceutical can be applied to any and all of the products. It is also worth touching on ordinary foods that can also be called nutraceuticals.

Dietary supplements

For dietary supplements regulated under DSHEA, a firm is responsible for testing and proving the dietary supplement it manufactures or distributes is safe and that the claims made about the product can be substantiated with adequate evidence to show they are not false or misleading. This means that dietary supplements are not subject to submission testing and approval by the FDA prior to their introduction. The only exception to this is for the case of a “New Dietary Ingredient,” defined earlier. Manufacturers are required to register themselves pursuant to the Bioterrorism Act with the FDA prior to producing or selling supplements. CGMPs for dietary supplements were published in June 2007, and these regulations deal with the identity, purity, quality, strength, and composition of the products.

Adequate evidence, noted above, typically means clinical trials or studies that are large enough and statistically meaningful to demonstrate the benefit of the supplement. Unfortunately, to develop trials large enough to prove these points is extremely costly, and many of the trials, whether performed by the manufacturer or by universities or other groups interested in the science of nutrition, produce results that are difficult at times to summarize with strong conclusions.

Before you think this should be easy, remember, people in any study group can have or not have many different levels of nutrition from their everyday diet, and increasing or changing a component of the diet may or may not produce a simple-to-understand result. When one does studies on a new drug, only one outcome using a very carefully screened group of patients is used in many of the trials, making the conclusions a little easier to reach.

Another way to understand some of the complexity is to think of drug interactions. No one studies drug interactions to any large degree. For a patient taking multiple drugs, it is up to the individual patient and her or his physician to monitor what is going on and whether she or he is receiving the multiple benefits of each of the drugs. For both supplements and drugs, the placebo effect also plays a role in the overall benefit. Reputable companies manufacturing, distributing, and selling dietary supplements typically rely on multiple studies or larger definitive studies that provide a good scientific basis for the claims they make.

The FDA publishes a commentary regarding claims that can be made for dietary supplements, which provides an overview of the claims that can or cannot be made. If a product claims to be a treatment, prevention, or cure for a specific disease or condition, it would be considered and regulated as a drug.

The safety of dietary supplements comes under the jurisdiction of the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) because they are in final analysis foods. This organization is charged with obtaining evidence by monitoring the marketplace. They obtain information from consumer and trade complaints, reporting of adverse events for products (a log detailing all adverse events is required by law for a manufacturer or distributor of supplements), and in unusual instances, their own laboratory analysis of the products.

Regulations, label claims, and confusion

One confusing aspect surrounding the labeling of dietary supplements is the DSHEA-required disclaimer statement, “This statement has not been evaluated by the FDA. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” This statement is required when a manufacturer makes a structure/function claim on a dietary supplement label. These claims generally describe the role of a nutrient or dietary ingredient intended to affect the structure or function of the body. The manufacturer is responsible for making sure a claim of this type can be proved. They are not approved by the FDA. In contrast, the FDA reviews and approves labeling on a drug. The disclaimer required under DSHEA tells the consumer that the FDA has not evaluated or approved the claim. The “…diagnose, treat, cure or prevent a disease…” portion of the statement tells the consumer the product is not a drug.

Another area of confusion in the marketplace over dietary supplements, the terms nutraceutical and medical food come from how advertisements for dietary supplements are regulated. Another agency, the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) is responsible for regulating advertising and infomercials about dietary supplements and most other products sold to consumers. The law and regulations for the FTC are different from those for the FDA. The two agencies work closely together many times on products and questions about these products, but the final application of specific requirements is different for the two agencies.

How a medical food is defined and regulated is different from a dietary supplement. The term medical food is defined as part of the Orphan Drug Act in section 5 (b) 921 U.S.C. 360ee (b) (3) as “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements based on recognized scientific principals are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA advises that it considers this statutory definition of medical foods to limit and narrowly constrain the types of products that fit within this category of food.

Without going into all the other details and requirements for labeling of medical foods, the easiest thing to keep in mind for these products is that they can only be used to treat a disease condition. They do not fall into the broader categories of foods for special dietary use or foods making health claims. They can only be used for meeting the special nutritional requirements posed by a disease, and they must be prescribed and administered under medical (physician) supervision. The term medical food does not apply to all foods fed to sick patients.

The FDA does not require a medical food to undergo premarket review or approval. Individual medical food products do not require registration with the FDA. For more information on all of these questions please refer to the FDA's Guidance for Industry: Frequently Asked Questions About Medical Foods (www.cfsan.fda.gov/guidance.html)

Question, and weigh facts

After reading all of this, I'm sure many of you are surprised about how complicated this subject really is. Something easy and simple, a food that benefits a person with many therapeutic properties like a drug appears to be a “no brainer” to understand. It is only when you start to ask questions about what it does, how it does it, and how do you prove it that the whole array of definitions and regulations suddenly make sense.

Dr. DeFelice really started something with the term nutraceutical. He wanted to convey how naturally occurring foods and the management of nutrition supplemented by other naturally occurring products could convey healthful and therapeutic benefits to people. Unfortunately a simple idea, treating disease with food, can be very difficult to understand when viewed in a practical, fact-based, clinically researched analysis. When a person wants to treat a problem with products occurring naturally or when someone wants to avoid traditional drugs for treatment of a disease or condition, hard study is required of many facts and opinions available before one can reach a conclusion about what is best for them.

Hopefully after reading this you will want to carefully weigh the facts about anything you are considering for improving your health or for treating a natural condition with “high potency” food as something that requires diligence and understanding to uncover the ones that make a difference in your everyday life.

-By Edward J. Bauer

Edward J. Bauer is Senior Director, Product and Package Innovation and Development for GNC, Pittsburgh, PA, and 2006 inductee into the Packaging Hall of Fame.

__________________________________________

Definitions:

Fortified/functional packaged food: This category includes packaged food to which health ingredients have been added. Fortified/functional packaged food provides health benefits beyond its nutritional value and/or the level of added ingredients wouldn't normally be found in that food. To merit inclusion in this category, the defining criterion here is that the product must have been actively fortified/enhanced during production. As such, inherently healthy products such as naturally healthy soymilk are only included under “functional” if additional functional ingredients (e.g., omega-3) have been added. To be included, the health benefit needs to form part of positioning/marketing of the product. There is one exception to the inclusion of fortified products in this category: Products to which vitamins have been added to replace vitamins lost during processing are excluded. These products would not typically be positioned on the basis of containing added nutrients.

Fortified/functional beverages: This category includes fortified/functional soft and hot drinks. When identifying fortified/functional products, we focus on products to which health ingredients (typically those with health claims) have been added. Fortified/functional beverages provide health benefits beyond their nutritional value and/or the level of added ingredients wouldn't normally be found in that product. To merit inclusion in this category, the defining criterion here is that the product must have been actively fortified/enhanced during production. As such, inherently healthy products such as 100% fruit/vegetable juices are only included under “fortified/functional” if additional health ingredients (e.g. calcium, omega-3) have been added. To be included, the health benefit needs to form part of positioning/marketing of the product. One exception: Products to which vitamins have been added to replace vitamins lost during processing are excluded. These products would not typically be positioned on the basis of containing added nutrients.